History at the Two Venues

About St. Etheldreda’s

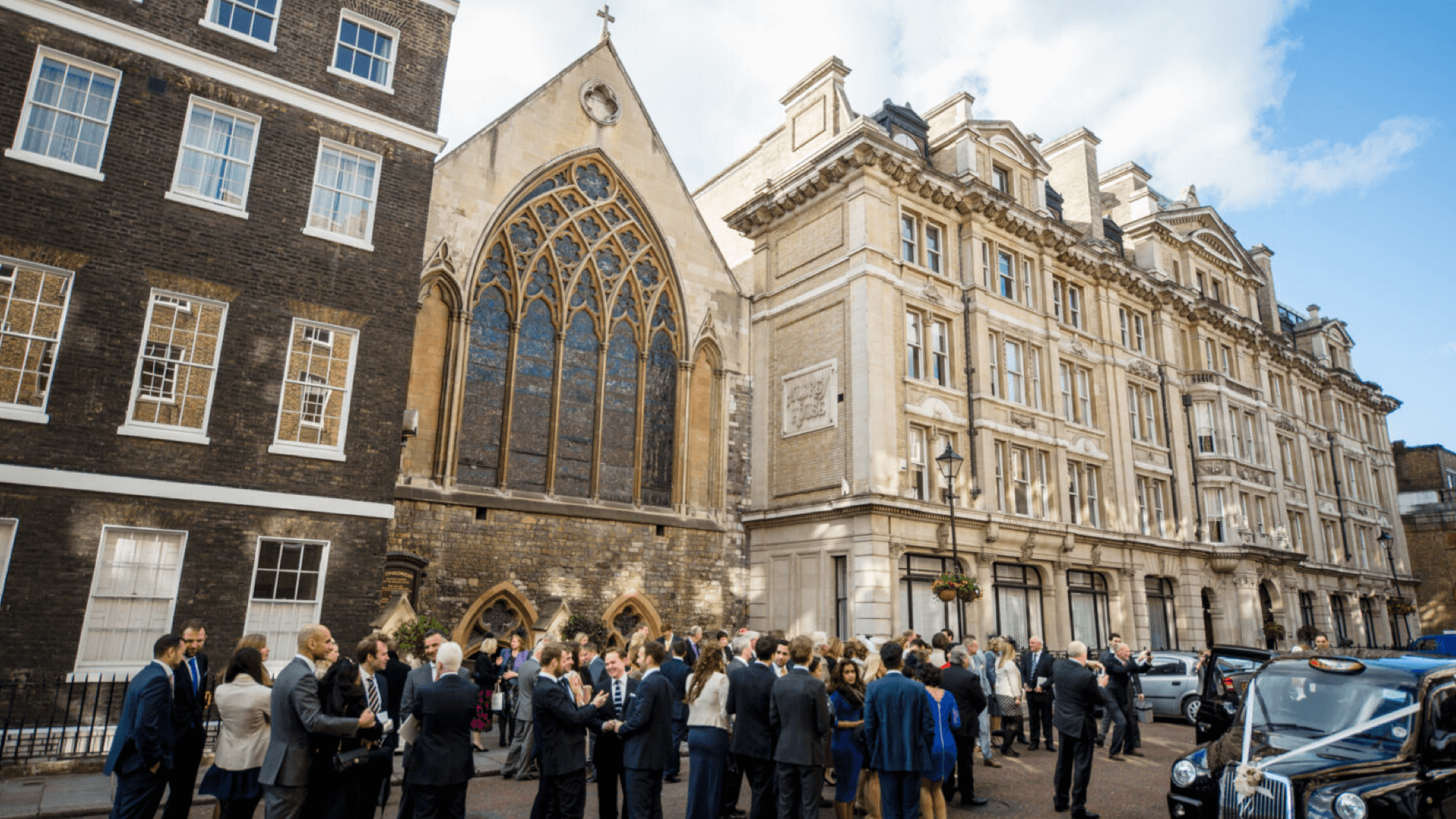

We feel very fortunate to be holding the wedding ceremony at a location with as much history as Ely Place and St. Etheldreda’s.

St. Etheldreda’s is the oldest Catholic Church in London, and, after The Tower of London and St Helen’s in Bishopsgate, the third oldest building. The chapel, built between 1250 and 1290, and grounds served as the London palace of The Bishops of Ely, a seventh century Catholic order founded by Æthelthryth, an Anglo-Saxon princess.

Æthelthryth died of a plague in 679 AD and was buried in Ely. Seventeen years later, when her body was exhumed, it was found to be perfectly preserved which was seen as a sign of her sainthood. She is still honored today in ceremonies and festivals at Ely Cathedral and at St. Etheldreda’s. Her remains were lost during the reformation, but it is said her perfectly preserved hand is in a casket on the wall to the right of the altar.

Æthelthryth died of a plague in 679 AD and was buried in Ely. Seventeen years later, when her body was exhumed, it was found to be perfectly preserved which was seen as a sign of her sainthood. She is still honored today in ceremonies and festivals at Ely Cathedral and at St. Etheldreda’s. Her remains were lost during the reformation, but it is said her perfectly preserved hand is in a casket on the wall to the right of the altar.

Because the Bishops of Ely pre-date England and the English monarchy, St Ethedreda’s and Ely Place have a long tradition of service to but independence from the crown. The grounds to this day remain a private road, and up until the late 20th century were considered the jurisdiction of Cambridgeshire, not the Metropolitan, police.

Throughout the period of the Plantagenets (1216–1485), the chapel was often used as a place of worship by the royals, and the crypt a place of feasting. This was especially true of the Duke of Lancaster, John of Gaunt, son of King Edward III and the father of King Henry IV, who, after a peasant’s revolt destroyed his home in 1381, lived there until his death in 1399.

Future royals similarly enjoyed using the crypt for feasts. In the mid-1520s, Henry VIII held a five-day feast there with Catherine of Aragon (John of Gaunt’s great-great-granddaughter) whilst they bickered and squabbled about their divorce.

The marriage between Henry VIII and Catherine of Aragon was eventually annulled in 1533, but Henry VIII’s distain for papalism and, in turn, Catholicism led to centuries of persecution against Catholics.

For most of his life, Shakespeare, who was raised a Catholic, lived in Blackfriars which is a short walk from St. Etheldreda’s. Inspired by visits there, he mentions the church and Ely Place in two of his plays (Richard III, 1592, and Richard II, 1595) and in several other writings.

In 1620, the Spanish ambassador, and close friend of King James I, Count Gondomar, leased St. Etheldreda’s and declared it Spanish soil so that Catholics had a safe place to worship, as Catholicism by that time in England had been outlawed. The tunnels and the unique jurisdiction forged over centuries provided harbor for secret meetings between Catholic sympathizers and Catholic priests who were being arrested and executed.

Though not a Catholic, the sanctity and independence of St Etheldreda’s attracted an influential English clergyman called Matthew Wren to worship there until he too was arrested in 1641 for questioning the authority of the puritans. Whilst incarcerated in The Tower of London, Wren appealed to his captors by promising that if he were to be released he would help organize and fund the rebuilding of nearby St Paul’s. Following his release in 1660, he kept to his promise and successfully argued that his nephew, Christopher, design it. Matthew died on the grounds at the age of 81 in 1667. Construction of St Paul’s started in 1675, but would not be completed until 1710.

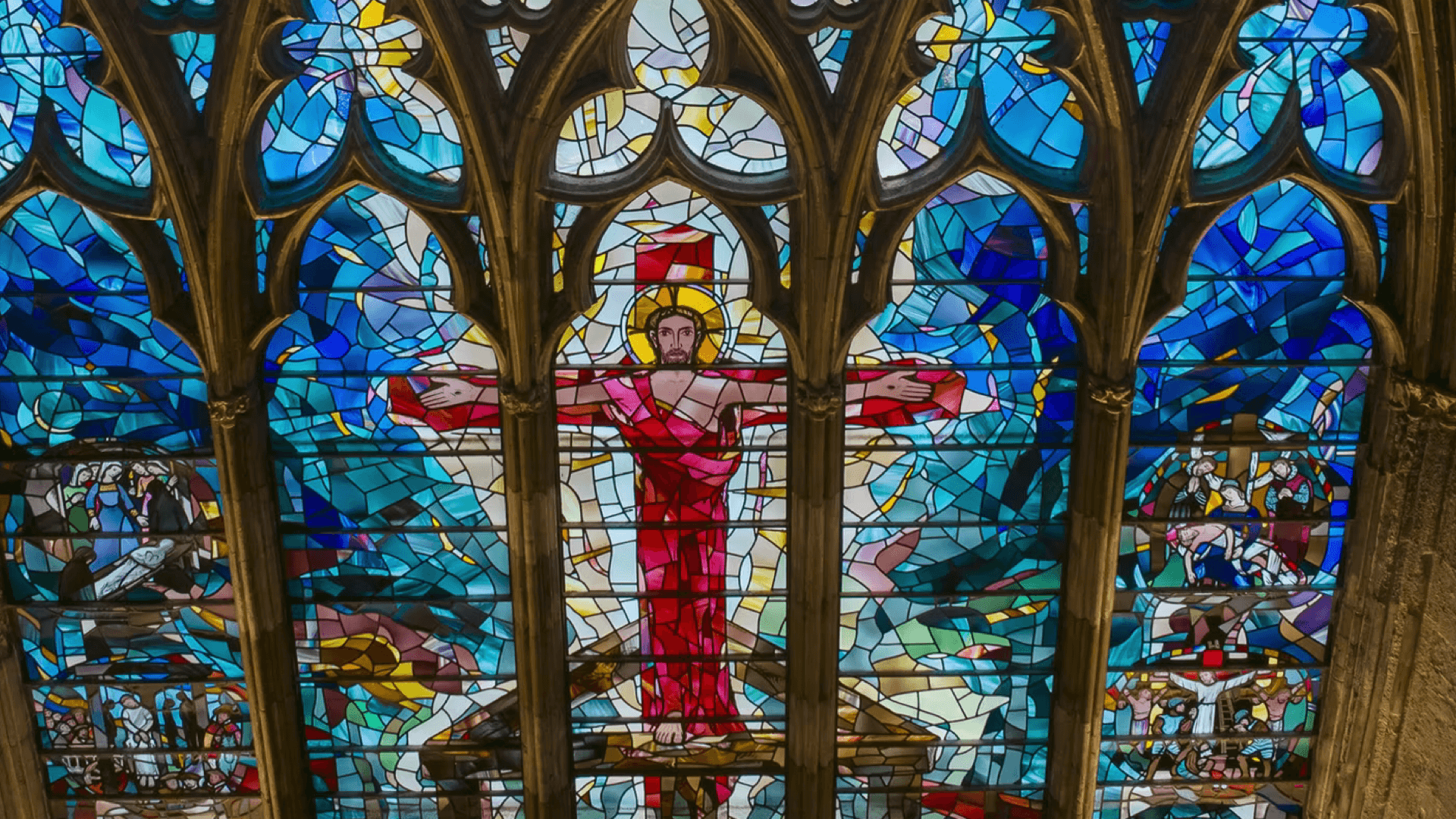

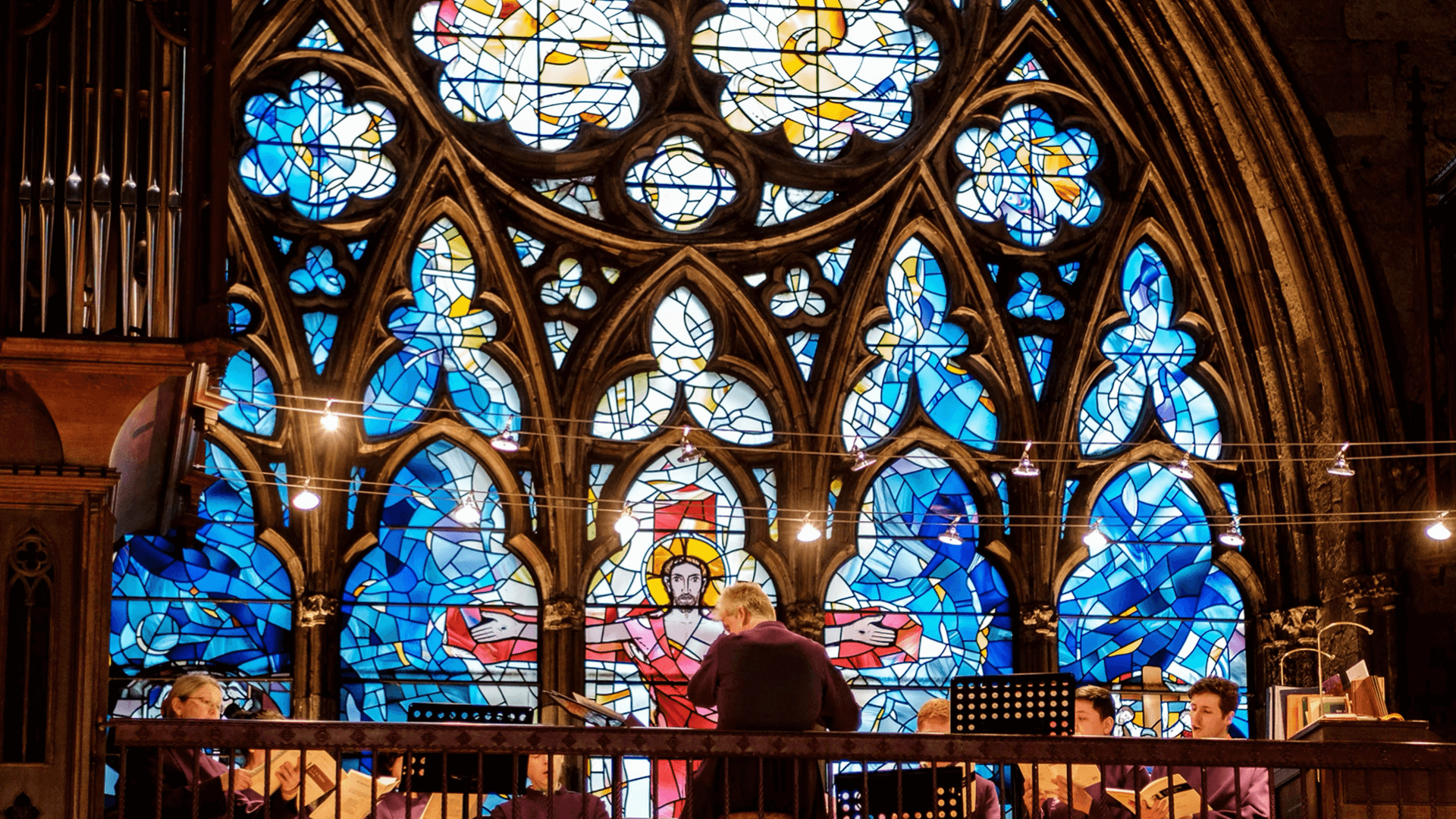

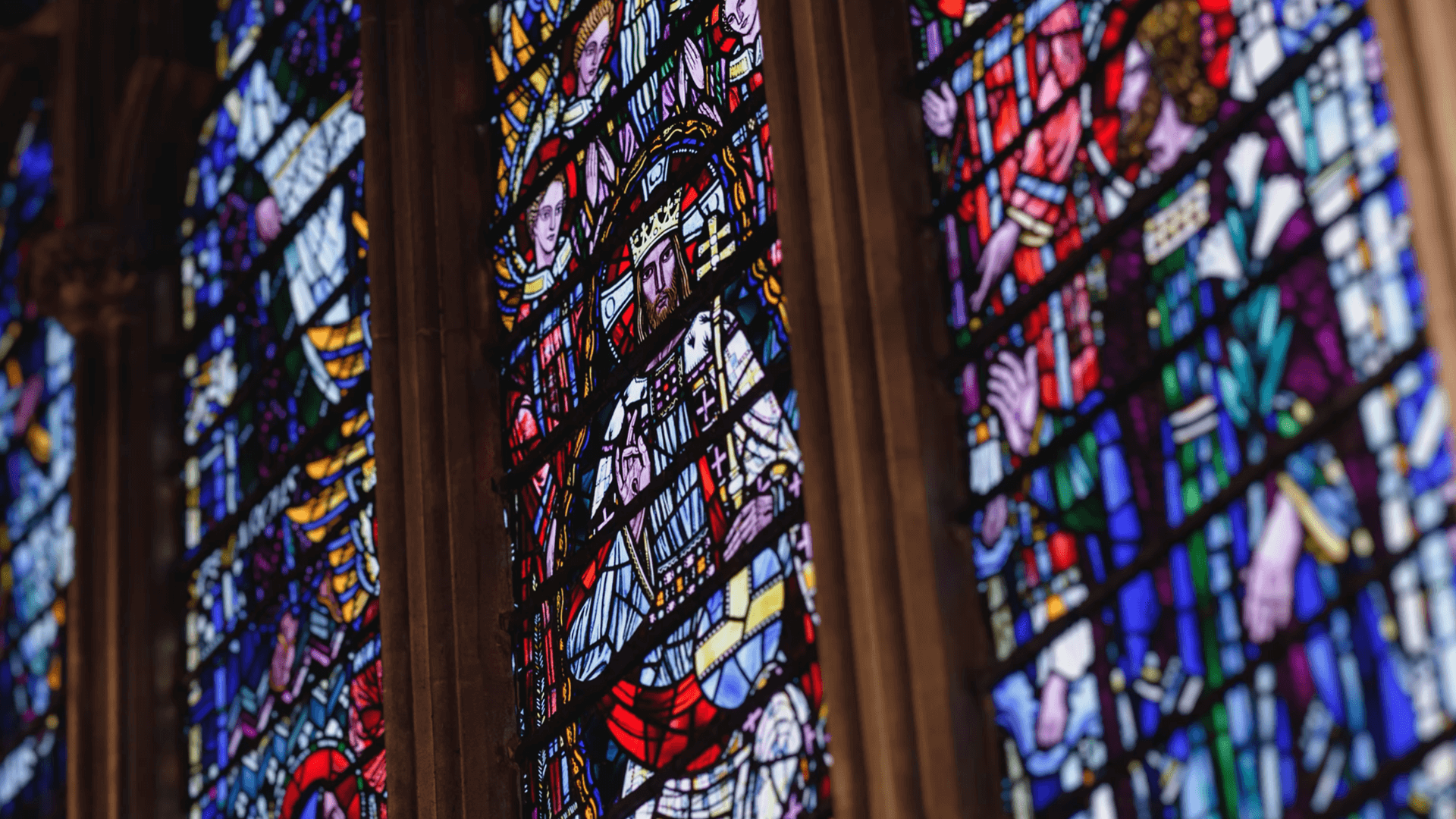

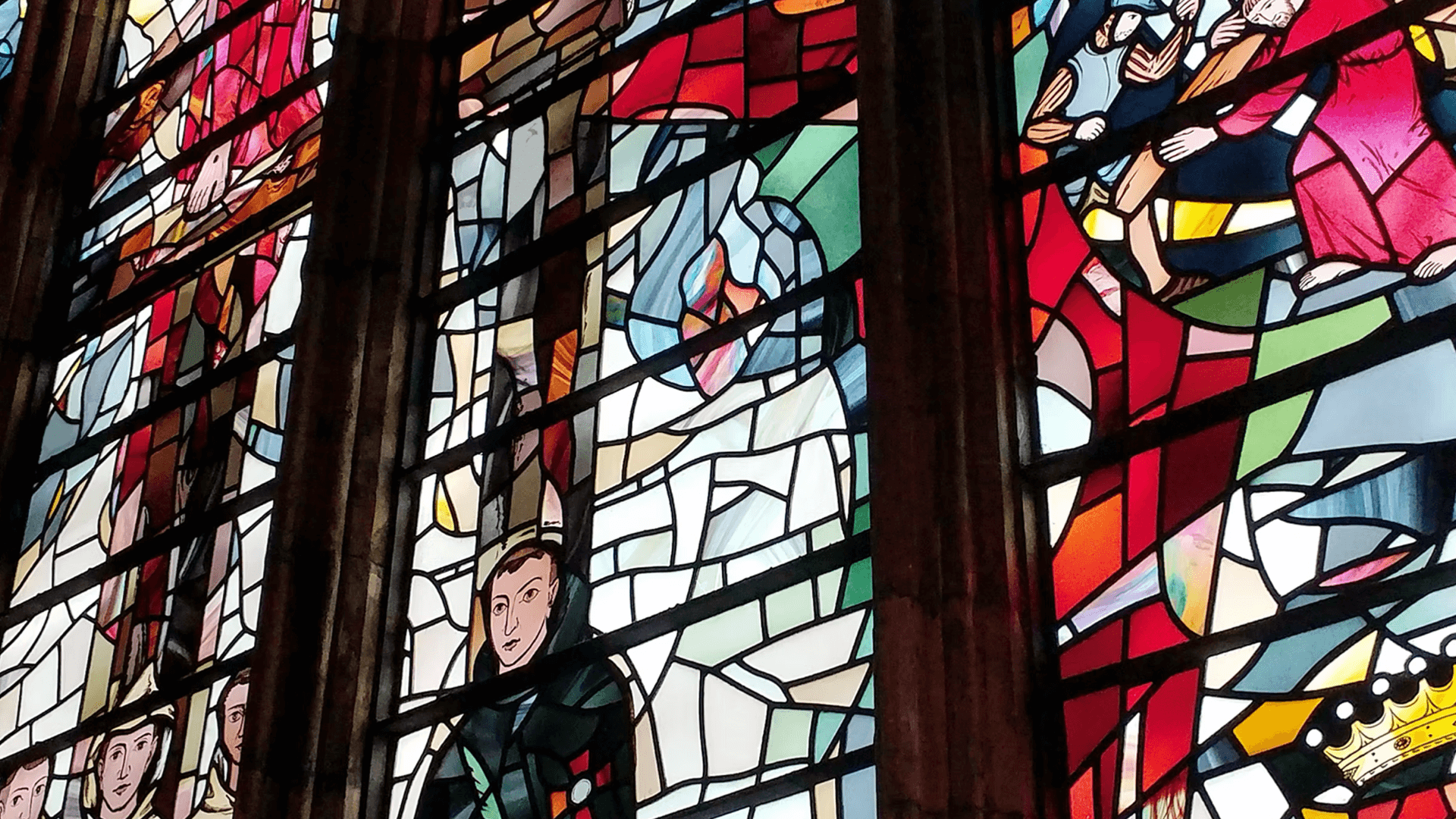

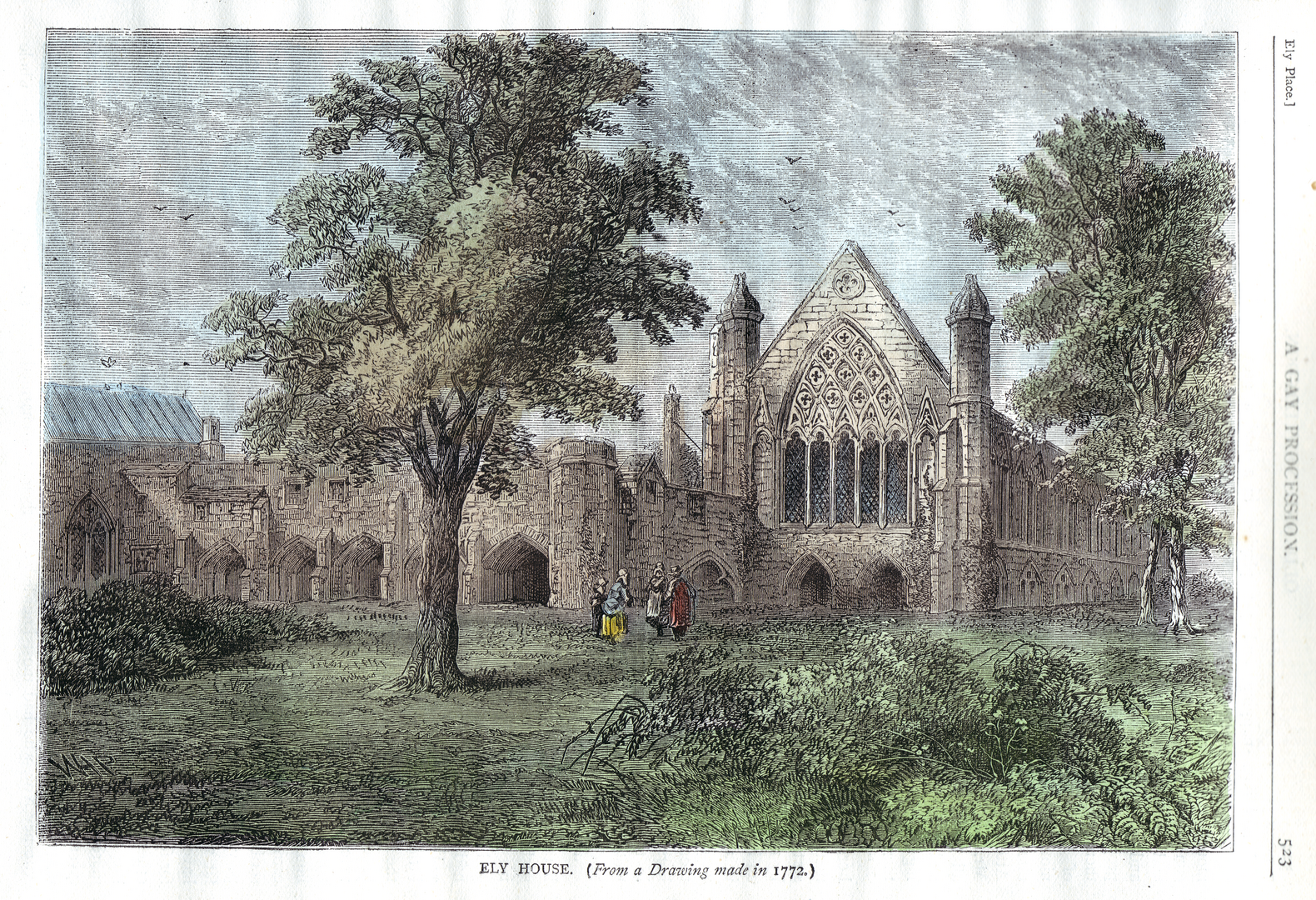

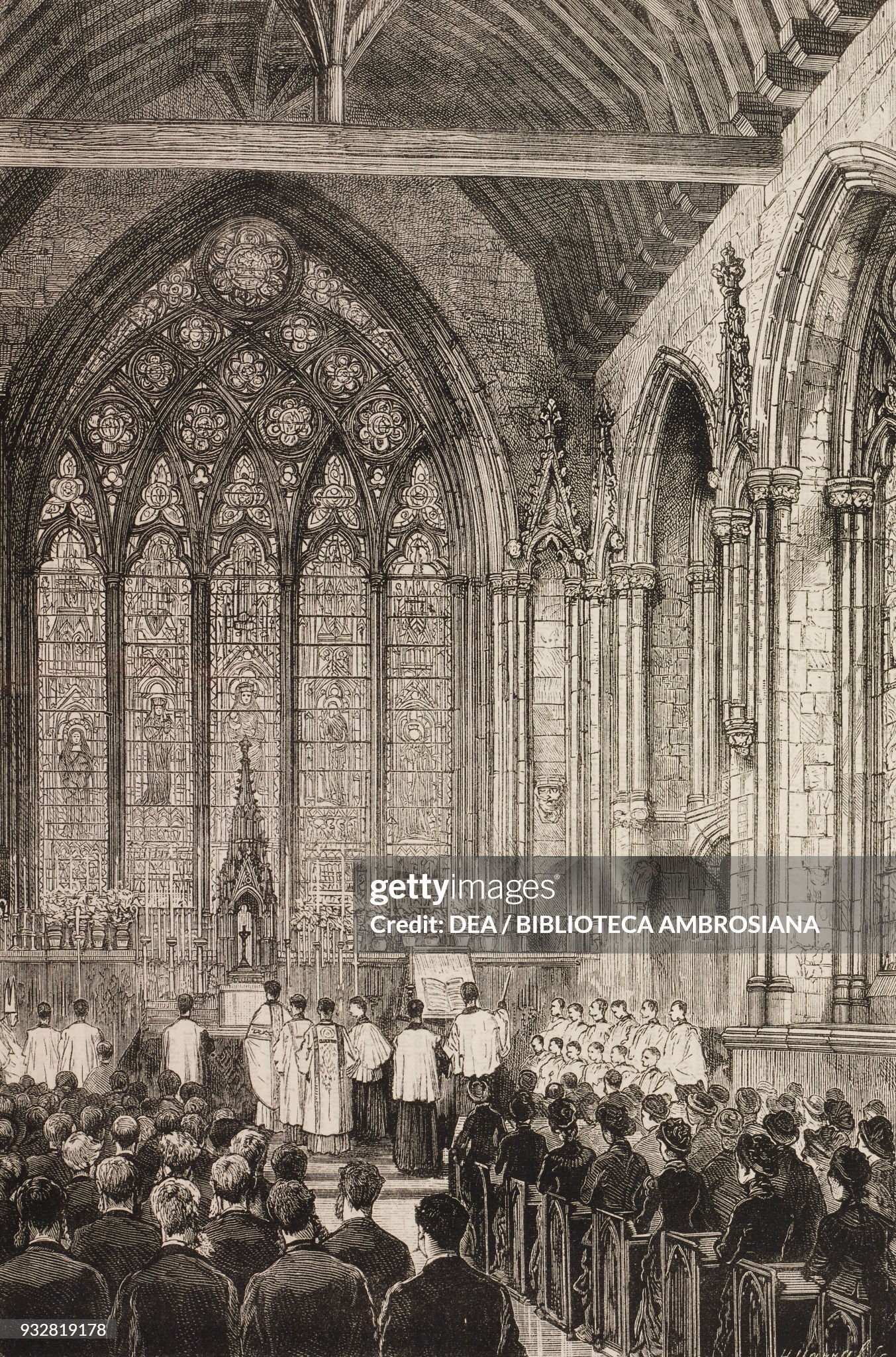

After Count Gondomar returned to Spain in 1622, it took many years for Catholicism to return to St. Etheldreda’s. During the English civil war (1642 to 1651), Ely Place was turned into a prison, and then a hospital. The crown and then Anglicans controlled the chapel during the 17th and 18th centuries. After some neglect, the chapel was put up for auction in 1874, and purchased for £5,400 by a Catholic convert called Father William Lockhart. Lockhart worked tirelessly to ensure the restoration work was completed to the very highest standard, and the stained glass at St Etheldreda’s that he commissioned are considered some of the most beautiful in London. When the work was completed in 1878, Catholic Mass returned to St Etheldreda’s for the first time in over 250 years.

The chapel is still a place of worship for Catholics and a venue for baptisms, marriage ceremonies and funerals. The crypt is still used for ‘feasts’ but in the form of corporate events rather than royal patronage. You can visit the crypt on your way in or way out from the ceremony. It is down some stairs on the right on your way in. Keep an eye out for the 8 foot thick walls that have kept the crypt intact for nearly 800 years, statues and stained glass that pay homage to the Bishops of Ely and the jeweled casket behind and to the right of the altar that may (or may not), contain the pristine hand of St Etheldreda herself.

Sources

A wood engraving of Ely House in London, including St. Etheldreda’s chapel, the only part of the building still standing. Originally produced by William Henry Prior, “Old and New London” (1873-1878), based on a drawing from 1772.

The hand of St. Etheldreda?

Entrance to the crypt.

“My Lord of Ely, when I was last in Holborn,

I saw good strawberries in your garden there;

I do beseech you, send for some of them.”

About The Hotel Russell (Kimpton Fitzroy)

Hotel Russell, now known as the Kimpton Fitzroy London, is a historic 5-star hotel located in Russell Square, Bloomsbury, London. It has long been an iconic part of London’s hotel scene, known for its grand architecture, rich history, and famous guests.

The hotel stands on the grounds that were once Baltimore House, a mansion built in 1759 by Frederick Calvert, 6th Baron Baltimore, using money from rent he received from abroad, having, at the tender age of 20 in 1751, inherited Maryland.

The Hotel Russell was designed by Charles Fitzroy Doll who was a renowned Victorian architect. His buildings often featured ornate detailing, classical proportions, and an emphasis on grandiose interiors. His association with oppulence and splendor gave rise to the phrase “all dolled up”. Of all of Fitzroy Doll’s designs the Hotel Russell is often considered his finest achievement. The dining room on the Titanic is almost identical to the Hotel Russell’s as Fitzroy Doll designed both.

The hotel’s striking terracotta façade was built by the same company that created the Natural History Museum’s exterior. It remains one of London’s best examples of late Victorian architecture. The exterieior includes effigies of 4 female monarchs – Elizabeth I, Mary II, Queen Anne and Queen Victoria designed by the famous sculptor Henry Charles Fehr.

Inside the hotel, there is a bronze dragon statue, believed to bring good luck. A near identical statue was on the Titanic, which has added to its mystique, and given rise to various tales about the dragon being a lucky charm that protects the building and its inhabitants.

The Russell Group, a prestigious association of 24 leading universities in the United Kingdom including Oxford and Cambridge (often compared to the Ivy League in the US) chose the name “Russell Group” as the founders started the organization by meeting in the Hotel Russell.

In popular culture, The Hotel Russell is mentioned in Andrew Lloyd Webber’s musical Cats during the song “The Journey to the Heaviside Layer”.

Shortly after opening in 1900

Natural History Museum

Lucky George